ONE WOMAN, ONE ACCIDENT, AND A SONG THAT MADE NASHVILLE STOP BREATHING

They say “Sissy’s Song” was never meant for the world.

It wasn’t born from fame or ambition — it came from heartbreak. Alan Jackson wrote it in the stillness that follows tragedy, when laughter fades and the only sound left is memory.

Leslie “Sissy” Fitzgerald wasn’t a celebrity. She never stood under stage lights or held a microphone. But to Alan and his family, she was something far greater — a quiet constant in their lives. She worked for the Jacksons, but more than that, she cared for them. She kept their home warm, their children smiling, and their days stitched together with grace.

Then one day, a phone call shattered that peace. A motorcycle accident had taken Sissy’s life far too soon. Nashville moved on as it always does — but Alan didn’t.

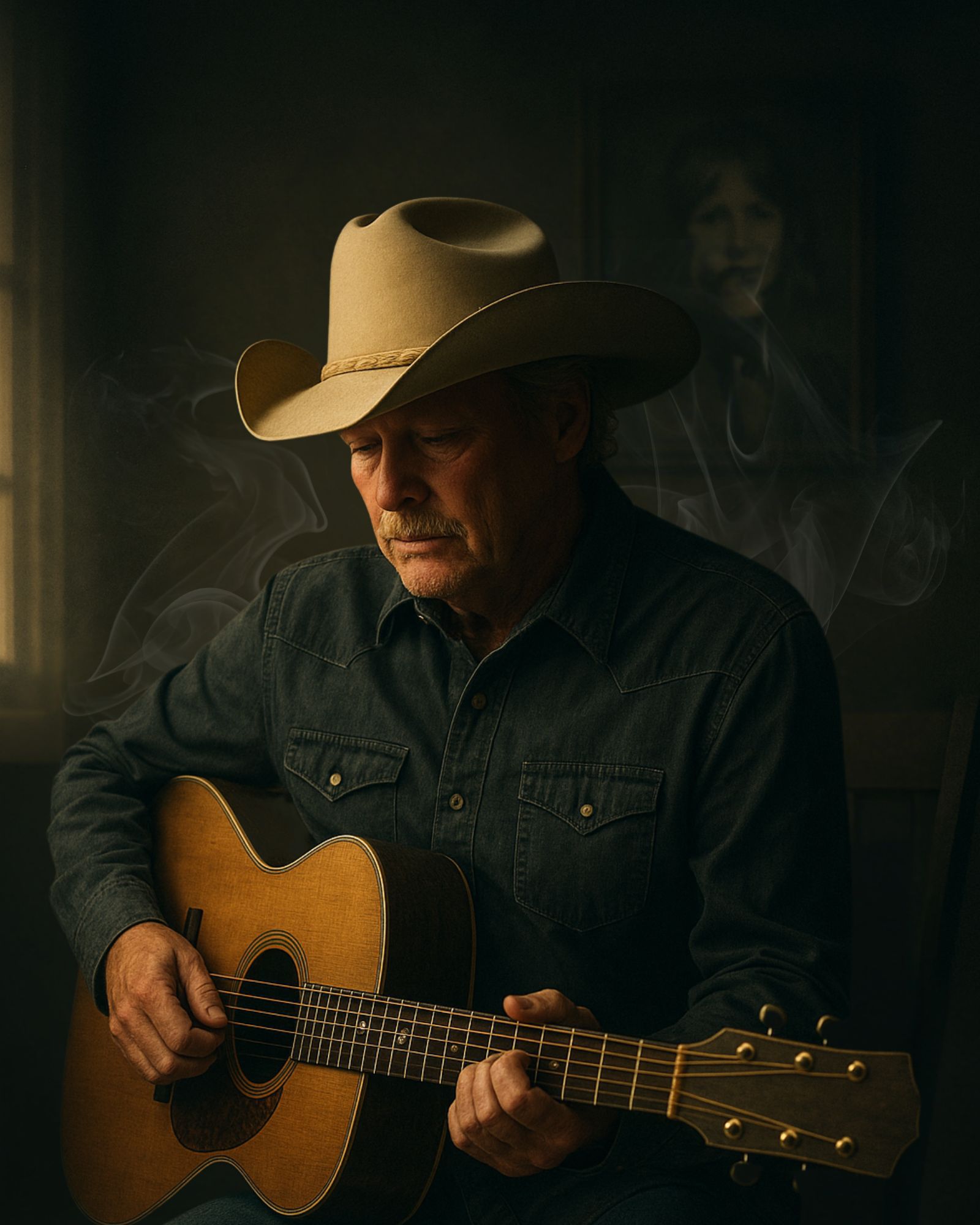

He sat alone with his guitar that night, not as a star, but as a man broken open. There was no studio, no audience, no band. Just the raw sound of wood and string, and the kind of silence that hums right before a prayer.

He sang only once.

“She flew up to Heaven on the wings of angels…”

Those words weren’t meant to leave the room. They were a farewell whispered through melody — a private eulogy that somehow became eternal. The recording played at her funeral, where tears replaced applause. Yet, grief has a way of finding its own stage.

The song drifted beyond the church walls, across radio waves, and into hearts that recognized the sound of love mourning its loss.

When “Sissy’s Song” finally reached the world, it didn’t climb the charts because of promotion — it rose because it was real.

Years later, fans still say they can hear something different in Alan’s voice on that track — a quiet break between faith and sorrow. It’s the sound of a man learning to let go, one note at a time.

And maybe that’s why it endures. Because “Sissy’s Song” isn’t just about death.

It’s about love that refuses to fade — even when the music stops.